The Gospel Passage this week is: St John Chapter 17 verses 1 to 11.

Life after lockdown.

John’s gospel is not an easy read compared with the other three: more Hilary Mantel than Hercule Poirot. But after you have puzzled over this rather impenetrable passage for a bit, a rather surprising idea emerges.

The Old Testament is a story of lockdown under the Law of a socially-distanced God, righteous, powerful, and sometimes vengeful. Here Jesus is offering a different picture, a God who is ‘family’, a God who is as intimate as spouse or sibling. What Jesus is saying, as he now makes preparations for his final journey, is that his followers will no longer be simply the people who hang on his words and gasp at his actions but they will become part of him, just as he is part of God. Such an intimacy means that the heart of a good and just God now beats in us, and we are part of God’s design.

What might this mean in the situation which faces us at this time?

They’re all saying it – sage scientists, newspaper pundits, neighbours, barrack-room lawyers: life after Lockdown cannot be the same as before. What will this ‘new normal’ look like? Everyone has their ideas. Will the climate crisis become a priority (and, as we in Markinch and Thornton prepare to become an eco-congregation, we are interested in that)? Will global co-operation and planning replace national one-upmanship? Will working from home become a recognised option?

Some people, though, go further. They suggest that, as we clap the front-line workers who help keep society healthy, safe and mobile, we could emerge from lockdown a kinder, more caring, and more compassionate people?

We might find this last prediction hard to imagine. Given the stories of inhumanity across the globe that dominate the breakfast news, and given the still prevailing theology of the Fall, we tend to see human nature, unless kept in check, as tending towards evil rather than good. Remember that famous novel of the 1950s, Lord of the Flies: a group of well-educated British children, including some choir boys, are marooned on a desert island; although they elect a leader and make rules, gradually they descend into vicious savagery.

But in the papers this week there was an extract from a new book which suggested the opposite outcome. It concerned six boys from the Pacific island of Tonga who had set off in 1965 on a fishing trip and were caught in a storm. Their sail was shredded and they lost their rudder. After eight days without food and water they made landfall on a small rocky islet, far from anywhere. It was fifteen months before they were found.

But the interesting thing is that this is not a novel but a true story.

The author had stumbled across an old newspaper cutting from 1966 and went looking for the boys. He found them and their rescuer, now in their 70s and 80s. On the island, they had hollowed out tree trunks to store rainwater, created a food garden, constructed a gymnasium with curious weights, made a badminton court, fashioned a makeshift guitar, penned some wild chickens whose ancestors had fed the island’s original inhabitants taken into slavery 100 years earlier. They organised themselves into teams of two, developed a roster. Yes, there were quarrels, but with compulsory time out these did not last. They ate fish, coconuts, seabird eggs, bananas, and poultry. One boy broke a leg, the others set it using sticks and leaves, and it was found, when they were rescued, to be perfectly healed.

But there is part of the story we haven’t told yet. There was no beach or landing place on the island; one of the boys swam ashore at great risk, the others followed. But before he dived in, he prayed. And every morning and evening of these long months, they sang and said a prayer.

What does this prove? We know that realistically things can go wrong. Perhaps it is essential that there is a righting mechanism that tips the balance. Christ died and rose and in rising took humanity into the life of a good and righteous God, one who seeks justice for the oppressed, the weak, and the marginalised. People who call themselves Christians are constant reminders of the innate goodness of a humanity which shares God’s nature. Their life and their worship daily hold out the option of a kind and compassionate society.

There’s one more thing to take from our gospel passage: it is in the form of a prayer. Jesus, having fully lived in the world and knowing at first hand the heights and the depths of the human condition, is praying for his disciples – and the symbol of Ascension means that this Jesus now prays for all humanity. It is a comfort and a relief, and sometimes even a lifeline, to know this.

This also is a true story.

Prayer

based on a prayer in a streamed service of Holy Communion 10.5.20

by the Revd Canon Ruth Innes, St Fillan’s Episcopal Church, Buckstone, Edinburgh

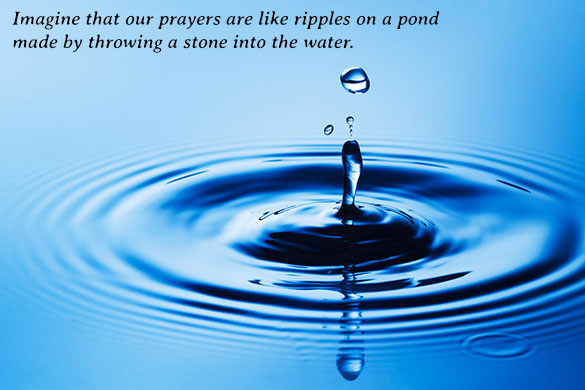

Imagine that our prayers are like ripples on a pond

made by throwing a stone into the water.

The smooth surface of the pond is broken

and we see the first circle appear.

In this circle are our families and neighbours,

those with whom we live,

loved ones whose photographs surround us,

those we long to embrace again;

and we pray for those around us and near us

who are sick, or alone, or frightened.

The circle spreads, to people in our wider community:

all we depend on, whom we see daily but don’t always notice.

We pray for all who are essential for our life in community:

teachers, shop workers, nurses, carers, drivers,

those who deliver our post, those who collect the recycling,

those who take risks daily on our behalf.

The circle spreads again, to those in the public eye:

those whose responsibilities put them under enormous pressure,

those who have difficult decisions to make,

when small misjudgements may be magnified,

who are trolled on social media,

who are criticised but cannot defend themselves.

The circle spreads again, right to the edges of the pond,

lapping against the bank,

when all our prayers meld into God’s creation.

We give thanks for our world,

for the beauty around us, for its rich provision;

may we not deface it, or plunder its bounty,

harming those who depend on it for their lives.

Our prayer today is only a small stone thrown in a pool,

a tiny offering of love in an ocean of need.

Take these prayers, Lord, and the prayers of others,

so that life, healing and hope may spread

to the furthest edges of the world.

Though Jesus Christ our Lord,

Amen.

Email: dgalbraith@hotmail.com